Workers Ownership and Profit-Sharing in a New Capitalist Model?

|

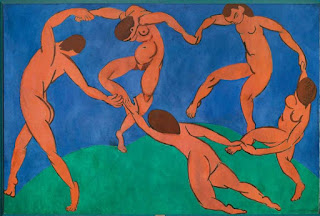

| Henri Matisse - La Danse - 1909 |

Text excerpts from Freeman,

R. B. (2015). WorkersOwnership and Profit-Sharing in a New Capitalist Model? (No.

267566). Harvard

University & © Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO) 2015

Richard B. Freeman holds the Herbert Ascherman Chair in Economics at Harvard University. He is currently serving as Faculty co-Director of the Labor and Worklife Program at the Harvard Law School. He directs the National Bureau of Economic Research / Sloan Science Engineering Workforce Projects, and is Senior Research Fellow in Labour Markets at the London School of Economics' Centre for Economic Performance.

The

challenge of extreme inequalities

Capitalism

today faces the specter of ever rising economic inequality and

perennial financial crisis. The fruits of economic progress are

increasingly concentrated on a small proportion of society – the

upper 1 %, 0.1 %, 0.01 %, 0.001 %, all the way up to the Forbes

billionaires. However fine the classification, the richest in each

group gained the most over the past few decades. The transmission of

productivity to the real wages of regular citizens that made

capitalism work for all broke down, with no obvious market fix or

political solution in sight. In the new world of financialization and

globalization, it is unclear how advanced economies can restore trend

increases in real wages, reduce or at least arrest the growth of

inequality and share more equitably the benefits of modern technology

and innovation or what, if anything, trade unions can do to help save

the day. Less than a decade ago – before the implosion of finance,

the great recession, sluggish employment recovery, and seemingly

inexorable concentration of income and wealth – economic

policy-makers and experts would have dismissed this assessment of the

problems facing capitalism as the ravings of a mad hatter.

Conventional thinking held that deregulated markets allocated

resources and determined prices and wages according to competitive

market ideals. New financial instruments had solved problems of risk.

If, by chance, something went wrong in the macro-economy central

bankers and finance ministers had the tools to restore full

employment or tame inflation. In a crisis, the IMF could bail out an

economy and guide it back to prosperity through judicious spending

and investment policies. Globalization was said to benefit virtually

everyone as long as markets were sufficiently flexible; and

flexibility was readily attainable by weakening labor protections.

[…]

The

OECD warned that inequality had bad effects on society and on

economic growth.The IMF reported that economies grew better with less

inequality! At the 2015 Davos meetings, groups with diverse

interests and ideologies worried about the future of a capitalist

system with huge growing inequalities. Trade unions denounced

“today’s business model” as bad for people but had no

suggestions of how to change the model.”

This

paper makes the case that the best path forward for capitalism is to

increase workers’ stake in the capital of their firm and in capital

ownership more broadly and that the best strategy for unions is to

take a lead role in promoting this development. Increased employee

ownership and profit-sharing is not the whole solution to inequality

or financial instability or the other problems that afflict advanced

economies. But it is a necessary part of any solution and the one

with the greatest potential for moving market capitalism forward in

ways that benefit all. Part 1 summarizes evidence that worker sharing

in ownership or profits is a viable business model that can reduce

inequality and improve economic stability. Part 2 examines the

benefits and risks to unions from promoting an ownership model and

contrasts a modern ownership/ sharing program with Sweden’s

1970s–1980s wage-earner funds. Part 3 reprises the main arguments.

Shared Capitalism Works for Firms and Workers

Firms

in which workers have an ownership stake or share in profits are a

normal part of modern capitalism. Tens of thousands of worker-owned

firms operate in advanced economies. The firms range from John

Lewis, the UK’s most successful retailer, to Spain’s Mondragon

conglomerate to China’s giant high-tech telecom Huawei to the US’s

12,000+ ESOP companies with their 13 million worker-owners. Many

high tech firms and start-ups have broad-based share ownership. Many

large firms subsidize stock purchase plans and offer stock options

for all workers. Profit-sharing or gain-sharing (where a firm

rewards workers for achieving a group target) are extensive. As a

result of these diverse practices, approximately 40 % of US workers

have a stake in the operation of their firm. Despite the EU’s

regularly endorsing greater worker financial participation in its

PEPPER reports, sharing modes of compensation are less extensive in

the EU than in the US.In Sweden about 11 % of firms and 43 % of the

largest firms offer employees share ownership schemes, but coverage

extends to only 5.5 % of employees. Approximately one fifth of all

companies offer all-employee profit-sharing schemes, mostly through

tax-privileged “profit-sharing trusts”.

How do firms fare when workers gain a larger share of rewards and decision-making?

Per the section title, the preponderance of evidence shows that firms with workers ownership or profit-sharing do better along many dimensions than conventionally owned firms. Many studies focus on US experience, with sufficiently compelling findings to have convinced the Center for American Progress’s transatlantic Inclusive Prosperity Commission to endorse policies to encourage greater worker ownership and profit-sharing in 2015. But enough evidence exists for EU countries to show that the benefits of the shared capitalist business model are not uniquely American.

On the firm side, a 2007 UK Treasury commissioned study (Oxera, Oxford, London) found that firms that shared rewards with workers through individual employee stock ownership schemes had about 2.5 % higher value added per worker than otherwise comparable firms without a sharing program.

A 2014 US study (Blasi, Kruse and Freeman (2014)) of over 1,000 firms seeking to make Fortune’s annual 100 Best Companies to Work For found that a disproportionate number of the 100 Best had some form of sharing arrangements: 17 % were ESOPs, 10 % were majority employee owned, 16 % give stock options to most employees.

The firms with more extensive sharing of rewards and workplace responsibility had high performance work practices and greater worker trust, which translated into higher market values relative to book value of assets.

On the worker side, the NBER’s Shared Capitalism study (Kruse, Freeman, Blasi, 2010) of over 41,000 workers in 14 firms found that more extensive employee ownership, profit and gain sharing, or broad-based stock options were associated with better outcomes for employees. Workers with a greater financial stake in company or group performance were especially likely to monitor other workers and to intervene to reduce the free rider behavior that plagues any group incentive system. More extensive sharing systems increased employee attachment, reduced turnover, and produced more employee suggestions for improvements.

What makes profit-sharing and employee ownership work are the workers, which opens the door for their unions to play a key positive role in these business forms.

To

what extent might expanding employee ownership/profit-sharing

restore the link between growth of productivity and growth of real

earnings, reduce income inequality, and improve economic stability?

[…]

The

most famous worker owned companies in Europe are Spain’s Mondragon,

a conglomerate of workers cooperatives (each worker has one vote as

owner) and the UK’s John Lewis, a 100 % employee owned trust that

operates retail stores and groceries. In 2015 Mondragon collaborated

with the US’s United Steelworkers to develop a union-cooperative

Mondragon-style model appropriate to the US. During the great

recession, John Lewis prospered, producing headline stories in the

British press about the large profit paid to its employee-owners that

would have gone to shareholders in conventional firms.

[…]

Comparing

employment fluctuations in the US in the 2008–09 recession and

ensuing recovery, Kurtulus and Kruse (2014) find that ESOP firms

reduced employment less in the downturn and increased employment less

in the recovery than other firms, thus stabilizing employment over

the cycle. Kurtulus and Kruse reference earlier studies of more

modest cycles that give similar results and give evidence that

suggests that ESOP firms survive longer but their data is not fine

enough to determine whether the greater rate of exit among

conventional firms is through mergers of buyouts or closure.

Comments